Nothing to Fear from the Multivitamin Study

If you’re concerned about taking your multivitamin, I think you can lower the concern. Is it still possible that there may be individuals who may have a unique set of genes and covariates that may increase the risk? Sure, it’s possible, but this study brought us no closer to finding out if that’s true. Here’s why.

The Issues with the Study

The problems lie in what the researchers didn’t do.

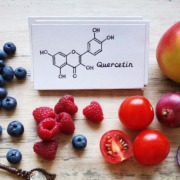

While the researchers used 13 different covariates, they didn’t break the data down by macronutrient or micronutrient. They used the Healthy Eating Index, but that ranks the quality of the diet from 0 to 100; that’s not the same as breaking the subjects’ diets down by intake of vegetables or antioxidants. It’s possible that someone who ate more vegetables could have higher antioxidant levels, which could contribute to getting too much of a nutrient by taking a multivitamin. The same would be true if they also were taking a complete multivitamin-multimineral and getting too much calcium or iron. That might have given valuable information to the people most at risk if there were such a relationship.

The researchers also did not give any explanation for mechanisms through which a multivitamin could increase mortality. That’s not unusual, because they didn’t examine any nutrient factors—but still, what was the point of saying there may be an increase in mortality, but nothing more than that?

The most likely explanation is that the results happened by chance because they tested multivitamin intake only twice early in the studies. Think of what you were eating 20 years ago. Has that changed? It’s reasonable to expect that some peoples’ habits changed, just as their dietary intake may have changed. We don’t know because they couldn’t go back and do the questionnaires every year or two, or even every five years. They suggest that this was a problem due to the latency of the data, and they were correct in my opinion.

The Bottom Line

This study illustrates the problem with going back to analyze data collected decades ago: you’re limited by the data you have rather than actually planning the study from the beginning. It’s an interesting observation after chunking lots of numbers, but it’s not meaningful in the real world due to the lack of ability to do an adequate analysis of the data.

What are you prepared to do today?

Dr. Chet

Reference: JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(6):e2418729.