Bioavailability Ends with Bioactivity

Here’s where we stand: we’ve digested a nutrient and it’s been absorbed into the bloodstream. How is it going to be used? How do we get the benefit of vitamin C, magnesium, alpha-carotene, or caffeine? Let’s take a look.

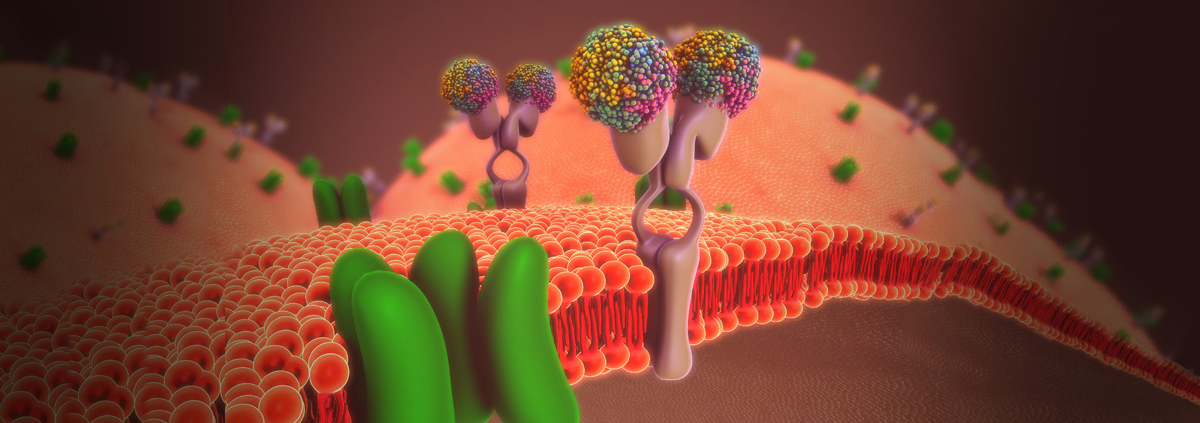

Many target cells have receptors that are specific to a nutrient, like a wrench that fits only one size of bolt. For example, when blood sugar rises after pasta is digested and absorbed, insulin is released from the pancreas. Insulin will attach to a specific insulin receptor on the cell membrane, and that will allow a glucose molecule to enter the cell to be used. Cells also have receptors for vitamin C to be absorbed into cells.

That’s fairly straightforward. The next step would be actually performing a function once the nutrient enters the target tissue. Let’s look at caffeine for example. There’s a genetic factor; one version of a gene can process caffeine quickly while a mutation of that gene processes it slowly. I can drink coffee and immediately go to sleep. Others may process it slowly and may not be able to sleep in the evening after a cup of coffee for lunch. Same nutrient, different effects on different people.

In addition, there are numerous enzymes that help make chemicals such as hormones or structures such as cartilage. If enough of an enzyme isn’t being manufactured or it’s blocked from being utilized, that can have an impact on how well a nutrient works. An example would be insulin; if cells are not producing enough receptors, or the receptors are resistant to insulin, blood sugar would rise. That leads to overall insulin resistance, one aspect of being prediabetic.

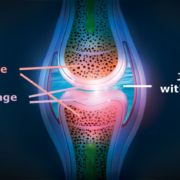

Another example would be the manufacture of glucosamine. The process requires fructose-6-phosphate and the amino acid glutamine; the first is a result of the breakdown of sugar while the later is the most prevalent protein-building amino acid in the body. The manufacture of glucosamine also requires an enzyme. If a person doesn’t make enough of that enzyme, that affects the production of glucosamine which then impacts the production of other forms of connective tissue such as cartilage, ligaments, and bone.

The Bottom Line

Every day there are new nutrition products introduced that are supposed to be better for you because more nutrients are available, but nutrition just doesn’t work that way. As I’ve tried to show you this week, the problem is that it isn’t quite as simple as what you see in Internet ads. Nutrients have to be digested, absorbed, and used by the body, and things can go wrong at any step along the way. Each individual’s body is unique and comes with its own idiosyncrasies and difficulties, and that’s what makes nutrition so complicated.

Maybe you’re thinking, “What’s the point if so much can go wrong?” What you have to remember is that most of the time everything works just as it should; not everything related to bioavailability goes wrong in every person. It’s also a matter of degree—maybe absorption will be cut by 50% or activity reduced 10%. I want you to understand why some nutrients won’t work as expected for a particular person, and why claims of better bioavailability aren’t a guarantee.

Yet we’re still here, aren’t we? We’re here because our ancestors survived. To steal a line from “Jurassic Park”: Nature finds a way.

What are you prepared to do today?

Dr. Chet

Reference: http://bit.ly/2raDviy